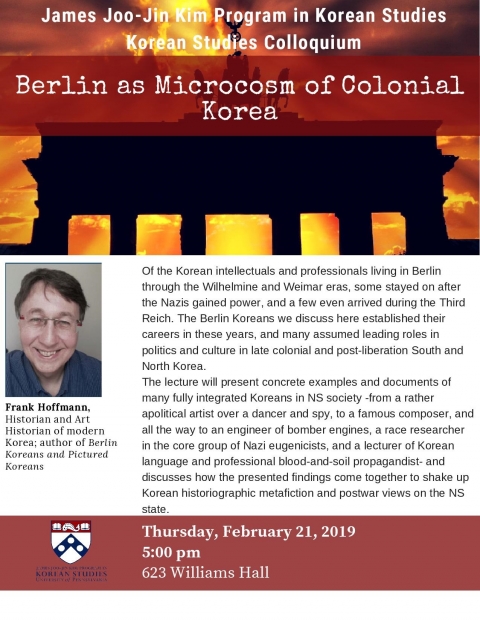

Korean Studies Colloquium

Williams Hall 623

Of the Korean intellectuals and professionals living in Berlin through the Wilhelmine and Weimar eras, some stayed on after the Nazis gained power, and a few even arrived during the Third Reich. The Berlin Koreans we discuss here established their careers in these years, and many assumed leading roles in politics and culture in late colonial and post-liberation South and North Korea.

The overwhelmingly anti-Japanese, internationalist, and socialist engagement of the politically and culturally vibrant Weimar years quickly vanished and was replaced by various degrees of collaboration with fascist culture and politics. Fully integrated in NS society and institutions, Koreans earned degrees, money, and fame, and—to varying degrees, depending on the individual—actively utilized NS institutions to shape their own careers, thereby supporting both Japanese and German fascists with their racist, militaristic, scientific, educational, cultural, and war propaganda efforts, in some cases to spring 1945 and beyond. The lecture will present concrete examples and documents for many such cases, from a rather apolitical artist over a dancer and spy, to a famous composer, and all the way to an engineer of bomber engines, a race researcher in the core group of Nazi eugenicists, and a lecturer of Korean language and professional blood-and-soil propagandist.

How do the findings presented here come together and shake up Korean historiographic metafiction and postwar views on the NS state? For once, the Korean case beautifully demonstrates how smooth, strategic and international Hitler's fascist regime actually operated, how even non-whites were actively involved in many core NS institutions. Furthermore, some findings suggest we take a fresh look at the sources of influence in late colonial Chosŏn and the immediate postcolonial period with its organizations, especially South Korean quasi-militaristic youth organizations. Finally, if we turn to art and culture, we may want to address the development of modernism in both Germany and Korea: unlike how most cultural histories depict it to this day, modernist art, dance, architecture, etc., were continuously practiced in Nazi Germany until the very end of World War II (despite the attack on “degenerate art” and the rhetorical creation of a “Germanic” aesthetic). International artists, performers, and architects were thus able to practice modernist forms and concepts within the fascist regime as long as their work was not contradicting fascist aims in terms of content. Looking again at Korea itself, we notice that the long-term, default representation of the colonial period modernization and Westernization process hardly finds its factual match in the work of overseas Koreans. Rather than directly reacting to and adapting modernist European forms and modes, these artists, musicians, etc., still seemed conditioned by the institutional framework back home, thus—and to an amazing degree—replicating Japanese colonial forms, genres, and cultural discourses, even while working right in the centers of European modernism.

James Joo-Jin Kim Center for Korean Studies

James Joo-Jin Kim Center for Korean Studies